This post originally appeared on Matt Weise's blog Outside Your Heaven.

Hideo Kojima's political mythologizing, which was so frustratingly absent from Metal Gear Solid 4, seems to have returned with a vengeance in Peace Walker. Returning to the Cold War era seems to have energized him and his team, with a game that looks to be more colorful and focused than MGS4's mish-mash of half-realized ideas. A lot of this might have to do with the fact that Peace Walker is clearly a game he wants to make, not one he thinks fans want him to make. No one asked for a euphoric, philosophical, Wagnerian extravaganza set against the backdrop of Nixon's resignation, but Kojima and Co. seem determined to deliver a bizarre, science-fiction version of the politically-charged 1970s whether you want it or not.

Cold War Punk. What else could you call it? MGS3, with its strange James Bond-inspired retro-futurism, certainly was this, and now that we have this label we could easy include things like the Fallout series. Such works exploit the iconography of that era to create fantastic worlds, alternate 20th centuries whose familiar symbolic landscapes are reconfigured into operatic counter-mythologies of world history. They mythologize the 50's, 60's, and 70's the way Sergio Leone mythologized the American West, turning it into a larger-than-life fantasy world that comments on the real world through exaggeration.

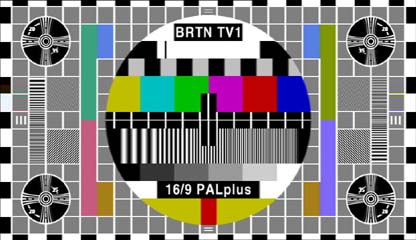

The symbolic universe of Peace Walker already seems a thousand times richer than MGS4. The use of television as a visual motif, of using what I can only assume is a riff on the emergency broadcast system (the TV images that was supposed to show if there was a nuclear attack), is instantly evocative. And the modification of the peace symbol, so that it looks like a bomber jet, perfectly embodies the contradiction at the center of the game's story, that war and peace are inseparable.

This is expressed in a Kant quote that presumably begins the game, that peace is an "unnatural" state, that the natural state of human affairs is war, that peace must be "created" by war. This doesn't seem to be a conclusion Kojima agrees with so much as a terrifying philosophical position that explains the madness of the Cold War. The title of the game is a reference to Metal Gear, the walking nuclear deterrent. By threatening war it ensures peace, thus it is the "peace walker", a walking machine that creates peace out of war. It is a monster that embodies the Kantian contradiction, just as the modified peace symbol does, as does the visual motif, seen in the Maurice Binder-style trailer, of one finger versus two fingers.

One finger extended can press a button and end everything, but raise another finger and you have "peace". The way the trailer ends, with the emergency broadcast system image, with the modified peace/war symbol at its center, being "pressed" by a single finger (as if it were a launch button), only to have a second finger at the last moment extend and create "peace", right before the TV image violently cuts and the world is plunged into (nuclear?) oblivion... this all represents a marvelously coherent appropriation of pop-cultural symbolic language to express what the game's about. It's the madness of nuclear brinkmanship distilled to a single, potent image.

It's because of this trailer that I did a little reading and realized that the peace symbol is, in fact, a direct reference to nuclear disarmament. It is an iconic abstraction of "N" and "D" in semaphore code, so the attempt to also associate "fingers" simultaneously with nuclear destruction and nuclear disarmament seems a fitting extension. If the difference between peace and war is one finger, how hard is it to extend that extra finger? But even then, what would it mean? One finger can press a button, but does two fingers necessarily mean peace? Kojima mentioned in an interview that even 'v' is ambiguous. It could be 'v' for victory. Is victory the same as peace? Is peace only created through victory, through war? Peace Walker layers all these double meanings on top of each other, so that they become a haze of contradictions we feel lost in.

It is a very Kubrickian view of war, and indeed Kojima seems to be drawing from Stanley Kubrick in both subtle and unsubtle ways. Not only is there a character in the game called "Strangelove", everything about the game seems to suggest war's absurd duality, a view that was most directly expressed in Full Metal Jacket, in the scene where Matthew Modine's character is questioned by his commander as to why he would wear a peace symbol on his helmet. His response is ""I think I was trying to suggest something about the duality of man, the Jungian thing..."

"Jungian" would be a good way to describe the insane symbolic universe of Metal Gear, with its bizarre characters, technology, and iconography that seem to rise out of our (or at least Kojima's) pop-cultural unconscious. Kojima's graphic design team is incredible, and they seem fascinated by collecting symbols and icons that elegantly capture the big ideas they want to explore.

Unfortunately, Kojima doesn't seem able to capitalize on these rich symbolic systems--to really back them up with content--as well as you'd hope, the way people like Alan Moore do in Watchmen (another work we might call Cold War Punk). This has especially been a problem lately. MGS4 was more about oogling tits and teary reunions than really examining in detail the socio-political implications of a war-driven global economy. Kojima sometimes seems to make the mistake (which, I'd argue, is a common pattern among fans-turned-practitioners) of confusing symbolism with content. At his best moments, his symbolic labels and operatic exaggerations serve to reinforce an underlying depth (The Joy and The Sorrow in MGS3) but at other times they insistent on a depth that just isn't there or--at worst--blatantly contradicted by crass presentation (the Beauty and the Beast Unit in MGS4).

What Kojima and his team are consistently excellent at is showmanship. What he's really promising with such ads is that his games will be about these ideas, and he has delivered enough in the past (mostly in MGS2 and MGS3) to still make such hype genuinely exciting. Most game makers don't even seem interested in promising such things. And even if Kojima doesn't keep these promises, maybe somebody inspired by his tantalizing sound and fury will.

UPDATE

It has been brought to my attention that what I thought was an artistic riff on the U.S. emergency broadcast system was, in fact, a PAL test pattern. The color bars that I showed above (known as the "SMPTE color bars") are the NTSC test pattern. The black and white image to its right, known as the "Indian Head test pattern", is what the NTSC test pattern was before the color era. Both test patterns have vague connotations of nuclear disaster in the U.S., because the Emergency Broadcast System used to show the test pattern on television and state that this is what would show in the case of a nuclear attack. I have personal memory of this, having grown up in the 80s in the U.S., which is perhaps why I and other American game makers associate the SMPTE color bars with national emergencies.

I had originally assumed that Peace Walker's test pattern was some combination of the SMPTE color bars and the Indian Head circles, but it's actually just a copy of the PAL test pattern. This makes me wonder if the theoretical practice of showing test patterns in the case of nuclear attack was as strong in PAL regions during the Cold War as it was in the U.S. Peace Walker seems to suggest it was, although I'd be interested to hear if this was (or still is) indeed the case.

Another possibility for the choice of the PAL test pattern is the association of "P-A-L" with "Peace At Last". PAL stands for "Phase Alternating Line" but when it was first introduced industry insiders sometimes joked it stood for "Peace At Last" or "Perfect At Last" because of how superior they felt it was to NTSC. Though somewhat oblique as a reference, it seems possible that this was one of the main reasons for the choice of the PAL pattern, since it would give Peace Walker's television motif the same contradictory connotations as the rest of its symbols. If the PAL test pattern simultaneously suggests nuclear attack and "Peace At Last" that seems to fit right in line with Kojima's dualism.

2 Comments

The first picture is based on the test pattern used by most PAL TV stations in the 80's, and I would assume the 70's as well. PAL was pretty much the standard outside of the Americas, Japan, Taiwan, and France. I grew up with that image (sans bomber/peace logo, of course), and it's familiar enough that I can immediately tell that some of the colors have been changed -- there's more red.

Why am I bringing this up? Well, TV standards always had alternate names known among broadcast professionals... NTSC was "never twice the same color", for instance, for obvious reasons. Because of PAL's widespread availability, its nickname was "Peace At Last."

Wow.