And the great owners, who must lose their land in an upheaval, the great owners with access to history, with eyes to read history and to know the great fact: when property accumulates in too few hands it is taken away. And that companion fact: when a majority of the people are hungry and cold they will take by force what they need. And the little screaming fact that sounds through all history: repression works only to strengthen and knit the repressed.

I had the good fortune of running into Naomi Clark, formerly of Gamelab, now chief designer at Fresh Planet at a serious games conference we both spoke at last weekend. Seeing her reminded me of the great talk she delivered with Eric Zimmerman at GDC last March entitled, "The Fantasy of Labor: How Social Games Create Meaning."

I had the good fortune of running into Naomi Clark, formerly of Gamelab, now chief designer at Fresh Planet at a serious games conference we both spoke at last weekend. Seeing her reminded me of the great talk she delivered with Eric Zimmerman at GDC last March entitled, "The Fantasy of Labor: How Social Games Create Meaning."

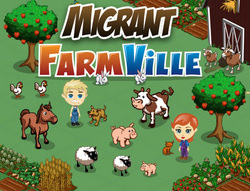

In their presentation, Clark and Zimmerman spoke about desire, about Suit's "lusory attitude" about cultural narratives, and specifically about how currently popular social game mechanics are related to a common western narrative about the fantasy of industrial labor - that hard work and determination will lead to wealth, popularity, fame, and success.

I remember hearing them speak and wishing they had pushed the idea just a bit further. They did argue that games could impoverish otherwise meaningful and important human interactions and cultural traditions. Specifically they talked about "gifting" in social games comparing the mechanic to the tradition of the Native American potlatch.

I think social games, as presently constituted on Facebook, often reinforce an all too familiar, and oppressive narrative of rags-to-riches determination in the face of arduous labor, that such work can lead to the "american dream" of wealth and prosperity, even as the chasm between wealthy and needy continues to spread, almost out of sight of one another. It also reinforces the notion that a community of wealth can support one another, driving a larger divide between the "connected" and the "disconnected."

Fiction

Imagine arriving in a new world, a land that seems to tip with the weighty overflow of opportunity. That very opportunity is why you came in the first place. You start with little, and you don't even know the language: the rules of their particular grammar. You experiment here and there, trying this and that to see what might work. Your work is by appointment, of course - work, rest, work, rest, work, rest, and gradually you begin to build a small little world for yourself, one farmhouse, or tree, at a time.For some reason, however, the next step ahead begins to seem farther out of your reach. You finger the lining of your pockets for loose change, wondering "could I afford that jacket," or "would it hurt too much to buy that candy?" You look around you and see others with their extravagant, opulent farms. How did they get so much? They must have worked so hard to get where they are, just like I am working. Soon, soon I will have that too.

And yet, with all your hard work and determination, some things still seem, always, out of your financial reach. You begin to realize that you can't join the country club down the road unless you know the right someone, unless you own the right car, or the right clothes. You are excluded on the basis of a class you didn't even know you occupied. You remember all your hard work, you look back at your modest farm and wonder. You try to remember why you came here in the first place.

You discover that there are people willing to loan you the money, whenever you want, so that you can buy what you need. You don't worry too much about it, because it is not money, you see, it is some strange kind of fictional currency. You know you will be held accountable for it in the future, but by then you'll have the biggest, brightest, most luxurious farm around, and you won't need to worry at all about finding money to pay back, that will be easy. Just keep digging, and working, and clicking and you'll get there. You do all this so that your kids won't have to.

But you still cannot seem to afford that next tree, or that next piece of fence. You splurge one day on a magazine, or watch some television, but all you see are beautiful, expansive, well decorated and lavish farms that make your home seem like a dust bowl. Click, click. Just keep clicking, digging, cleaning. Work hard and all this can be yours.

Non-Fiction

A reported 2% of the social game audience accounts for a vast majority of the money made by Facebook game developers. So called "whales" are players with enough discretionary funds, or perhaps a lack of economic discretion, to be spending money on in game items. These players live the Facebook dream, building massive farms and "winning" the games' economic systems. What of those who cannot spend with the same freedom, or worse, those who are encouraged to spend what they do not have?

A reported 2% of the social game audience accounts for a vast majority of the money made by Facebook game developers. So called "whales" are players with enough discretionary funds, or perhaps a lack of economic discretion, to be spending money on in game items. These players live the Facebook dream, building massive farms and "winning" the games' economic systems. What of those who cannot spend with the same freedom, or worse, those who are encouraged to spend what they do not have?

Please understand that I am not insinuating that there is anything nefarious or insidious about current social game design on Facebook, per se, on a commercial level. I do not intend to suggest that if these developers have a market they should not avail themselves of it.

However, I do have deep concern about how our cultural products can have a tendency to reinforce, or re-tell narratives that may have a negative effect on society. I have a lot of concern about games especially, as I worry that "play" is becoming more and more commercialized and commoditized.

Suffering a failing Farmville farm pales compared to the struggles of poor Americans attempting to scrape out an existence, pushing against an economic and social system that continues to undermine their very survival. However, the rhetoric of hard work as the primary solution to poverty, helping to keep wealth concentrated in the hands of a staggering minority, can be found in many nuanced, even un-intentioned domains, like Facebook games.

Why do games specifically concern me? Besides the fact that I work at a game lab, and study games as a job, I am concerned about how a culture's stories are written. We need look no further than popular sports in America to see how games and the culture that surround them are tightly woven into the fabric of our collective experiences. People argue, evangelize, and hypothesize on the myriad "measured" effects of games on individuals for learning or behavioral change, and regardless of how the pendulum seems to be swinging on any given day, we must wonder how Facebook games may be reflecting or reinforcing a social status quo that has many suffering while few thrive.

No, Facebook games are not responsible for poverty, of course not. But maybe with each mindless click, with each laborious click, we are replaying, in part, the story of so many who wanted to work and could not succeed, despite earnest effort and serious struggle.

This post can also be found at Abe's blog, A Simpler Creature.