In the recent, but not immediate, past, a few devel-oggers were discussing trying to maintain an archive of MUD history. Raph Koster, Richard Bartle and Brian Green (among others) talked about the difficult balance of relevance and authority in trying to get MUD history documented on wikipedia. While there appeared to be (in common Wikipedia fashion) some sort of compromise put together (in the sense that no one left happy), it left me thinking about the enormous difficulties in trying to get a decent, much less accurate, archive of games. I'll only tackle a bit of it, but I had to tip the hat to the source of the concerns, and it revolves around (surprise) us.

|

This page contains all entries posted to GAMBIT in March 2009. They are listed from oldest to newest. February 2009 is the previous archive. April 2009 is the next archive. Many more can be found on the main index page or by looking through the archives.

|

Games' Social History

GAM3RS the Play: A one-man show about the secret lives of gamers

Some folks from GAM3RS the Play visited the GAMBIT lab today. Their production will be performed at the MIT Museum (map) for two nights: March 13, Friday 8 p.m. Doors open at 7 and the event is free! The hour-long show will be followed by a half-hour discussion with the actor and writers about gaming and the theatre. Try to arrive early so you can get a good seat! Synopsis Work sucks for tech-support operator Steve Jaros. He's overqualified, underpaid, and around-the-clock dealing with vacuous customers, a Medusa-like boss, and an arrogant cubicle mate. But what they all don't know about Steve is that he is about to save an entire kingdom from death at the hands of their murdering neighbors. He is about to lead an army of thousands into a dangerous land to take back their source of power. He is about to become the most powerful warrior ever to live among men . . . online. With the help of a blue dwarf, a dark sorceress, and a disobedient page-boy, Steve (a.k.a. Boreus the White Knight) must lead his people to victory over the elven kingdom while answering phones and hiding his true identity from his patrolling supervisor. Can Steve successfully live in fantasy and reality at the same time? From the Brian Bielawski, the lead of the play: I feel that most of the magic is there because GAM3RS is based on my family. Entirely. (Think about all the implications of that as you watch it.) The rest of the magic comes from the whole gaming population for whom it was written. Long considered "weird" or "immature," gamers often get the short-end of the social stick. I created this piece to show that maybe, just maybe, gamers operate on a higher mental plane where the limits of the body and the "real world" are overthrown by the imagination. I have to think that way. After all, I'm one of them. From Gregory Wilson, curtainup.com, Brian Bielawski and Walter G. Meyer get so much right about the life of a gaming geek, here embodied in the character Steve (played believably by Bielawski), an MIT dropout who rules the universe of an online role-playing game and works a real life tech support job to support his virtual one, that the non-gaming members of the audience which find his behavior so bizarrely funny would probably be shocked to learn how accurate the portrayal actually is. What's fun about this show is that it packs more inside gamer/techie/webhead jokes into an hour than seems possible without leaving the 'outsider' part of the audience behind, and thus everyone gets to have a good time. Both gamers and non-gamers alike will enjoy its humor. Contact Brian Bielawski for more details. Why Am I Jumping?

Jumping is a mechanic so pervasive that we rarely stop to think about it. It has gone from the defining trait of a genre (platformers) to being included in all manner of action games, adventure games, and first-person shooters. As a means of traversing space it is nearly universal in video games, but in every day life it is nearly absent. How often does an average adult actually jump over something? Adult jumping is limited to hopping over puddles, which is a far cry from leaping over pits and on to platforms suspended in midair. How has this mechanic become so ubiquitous in video games? One potential answer lies with imitation. While they were not the first video games where you jump over enemies and onto platforms (an honor which may fall to Donkey Kong), the Super Mario Brothers games on the NES were hugely successful. This success spawned a wealth of imitators, leading to countless games where jumping over things was the primary means of interaction. That the Sega Genesis came with Sonic and the SNES with Super Mario World only further ingrained platforming in the gaming consciousness. While the success of these games may help explain the ubiquity of jumping today, there is the still question of how the mechanic came to be in the first place. Because early video games were two-dimensional, they were limited in choice of perspective. For the most part they had to be a top-down view, as in Adventure:

Or a side view, as in Pitfall:

Top-down games had odd perspective issues in that characters were typically drawn as seen from the side, not from above, as in Dark Chambers:

In a side view perspective game featuring a human avatar, you run into the problem of movement. In shooters like Defender the ship can simply fly in all four directions, because (in theory) that's how spaceships move. But a person is bound by gravity, and simply walking back-and-forth along the ground is not terribly interesting. Burgertime solves this by having multiple platforms connected by ladders: if an enemy is approaching, you can spray them with your pepper, or try to out maneuver them by moving to a different platform. The pepper only sprays directly in front of you; doing nothing but would get old fast. The fun of the game comes from the multi-layered levels. On the other hand, in games like Donkey Kong and Pitfall jumping is the main method of avoiding hostile entities. In other words, jumping provides another way for a gravity-bound person to move vertically, hence making use of the limited 2D space. Of course in the real world we avoid things like rogue barrels and hostile mushrooms by simply walking around them, so jumping in a 2D game might also be thought of as an abstraction of depth.

Burgertime Of course all of this is highly circumstantial and somewhat arbitrary. Besides, board games with jumping long predate video games and have developed all over the world. In his fascinating book The Oxford History of Board Games, author David Parlett devotes an entire chapter to games where one piece captures another by jumping over it (the following information is taken from Parlett's book). According to Parlett, the earliest game known with this mechanic is Alquerque: the game is described in a manuscript written in 1283, and may be the game called Qirkat mentioned in Kitab-al Aghani, an Arabic book of songs and poetry probably written before the author died in 976. Alquerque is largely accepted as the predecessor of what is called Checkers in the United States, and Draughts (or a variation thereof) in Europe. However, similar games have been found all over the world. Games such as Konane (Hawaii), Siga (Egpyt), Dablot Prejjesne (Sweden), Tobi-Shogi (Japan), Kolowis Awithlaknannai (Mexico), and Koruböddo and Lorkaböd (Somalia) all feature jumping capture. The long popularity and widespread use of jumping indicates that the mechanic itself has some sort of intrinsic appeal. People tend to have positive associations with height, a topic explored by Lakoff and Johnson in Metaphors We Live By. Lakoff and Johnson refer to such associations as "Orientational Metaphors." For example, in Christianity Heaven is described as somehow "above" the Earth (as in the geocentric model of the universe that long dominated European thought). Our language expresses the same idea, with phrases such as "jumping up and down," "on cloud nine," "free as a bird" or simply "things are looking up." The opposite is true: Hell is underneath the Earth, we feel "down in the dumps" or "under the weather." (There are of course a few exceptions, such as "I'm down with X" or "high on Y," though whether these are positive or negative phrases depends on who you ask.) This psychology is not limited to humans: many dog behavior experts say that when your dog jumps on you she is being dominant, trying to put you in a submissive position within the pack. In season two, episode three of The Dog Whisperer ("Buddy the Animal Killer"), Cesar Milan recommends stepping over your dog to assert your position as pack leader. In his words, "over means dominant." When a game piece jumps over another, it is in a superior position than its Earthly (boardly?) victim. The act of jumping your piece over your opponent's has an intrinsic satisfaction regardless of the in-game effect; this simple pleasure is extremely evident when watching beginners play Street Fighter. They jump frequently, almost constantly, relishing the motion: kicking your opponent is less satisfying than leaping into the air and then kicking him. That jumping leaves you extremely vulnerable is fairly obvious yet totally ignored. In his new book Game Feel, Steve Swink presents a picture of Super Mario Brothers tracing Mario's movements: his jumping creates a curved, arcing line. For Swink the shape of Mario's jumps have an intrinsic aesthetic quality: "Whether it's the motion of the avatar itself, animation that's layered on top of it or both, curved, arcing motions are more appealing" (306). There is more to jumping than psychology and aesthetics, however. In many games jumping is fun because of the associated risk. In a Mario game a mistimed jump will send you into a pit or cause you to collide with the enemy you intended to stomp on. In the old Sonic games your speed increased that risk, as a single jump could carry you through several screens worth of space, leaving you unable to tell where and on what you will land. This may be the reason the new Street Fighter player jumps so insistently: they are playing to have fun, not to win. Jumping can mean power not just over an opponent but over the environment itself: would Master Chief seem so powerful if he could not jump over a small rock or fence? The ability to jump in a first-person shooter gives the player more control over the environment, which makes the game feel less linear: jumping out of a window is more satisfying than backtracking to look for stairs. Jumping was frequently used in later 2D beat-em-ups to create the illusion of 3D space. In these games the player primarily moves in four directions: left and right, towards the player and away. Jumping adds height, so the player now feels like they are playing in three dimensions, as in Battletoads. The same could be said of first-person shooters: without the ability to jump you feel stuck to the ground, as though you are a 2D entity in a 3D space. BattletoadsThat jumping has been a part of games for so long indicates that it appeals to players on a very basic level. When studying video games it can be easy to forget that games have thousands of years of history behind them, and that is a long time for a mechanic to remain fun. Jumping's prevalence also suggests a strategy for inspiration: do other common themes in language, myth and psychology exist? And if so, can they be adapted into a game? Vote for CarneyVale!

The IGF Audience Award is open for voting from now until Friday, March 20th. please vote for our game, CarneyVale: Showtime! CarneyVale: Showtime is an Xbox Live Community Game, so you'll need a networked Xbox 360 to download and try it out. You can choose between the free trial version or the full $5 version. From the Xbox Live Game Marketplace, look under the "Community Games" and "Contest Finalists" section to find our game. The competition is incredibly stiff this year, with other fine games like Retro/Grade, Dyson, Brainpipe, The Maw, IncrediBots, Osmos, Musaic Box, Cortex Command, Coil, The Graveyard, PixelJunk Eden, Mightier, You Have To Burn The Rope, and Between all currently playable and eligible for the Audience Award. The full list of IGF finalists is available at the Independent Games Festival website, and we're looking forward to meeting them at GDC. The Pleasures of Old School Resident Evil - Narrative Confusion

WARNING: What follows will probably only make sense to people who have played and finished most of the cardinal Resident Evil games. Read at your own risk.

"It's up to us to take out Umbrella."

--final line in Resident Evil 2

In my imaginary alternate universe where Resident Evil remained consistently interesting, the next game would have been exactly that: taking out the Umbrella Corporation, or at least seriously attempting to. This is sort of what Code Veronica did, but beginning with RE3 the series began its side story-obsessed, franchise-milking holding pattern that completely derailed the narrative momentum of RE1 and RE2. If we can take Code Veronica as the "real" RE3 (which, from my understanding, is what it was originally intended as) then "RE3" and RE4, at least conceptually, extend directly from Leon's line at the end of RE2. Code Veronica picks up Claire's thread as she attempts to infiltrate Umbrella's Paris branch, and RE4... well my suspicion is that RE4 at its genesis was a companion piece to Code Veronica, a game that extended the globe-trotting pursuit of Umbrella established in RE2. That's the rationale for the European location, and I imagine the original story was similar to the final one except that it was Umbrella (and not the locals) who were masterminding things. If RE4 had been released soon after Code Veronica, instead of the endless remakes and side-stories, I imagine that's what it would have been. However, Capcom kept it in development for years and when it was finally ready they had more or less lost the thread established in RE2, hence RE4 feeling more like a reboot than a sequel. This resulted in a strange experience for anyone who actually remembered RE2, since RE4 finally brought back Leon yet dropped Umbrella out of the story completely. Since Leon's entire motivation at the end of RE2 seemed based on taking down the Umbrella Corporation, it left him with no personal motivation in RE4. This is why RE4 felt so frustrating to me. As a follow up to Code Veronica (which felt very much like a sequel to RE2, in spite of its shortcomings) RE4 is almost entirely non sequitur. Story-wise it feels like RE4 should have been a side story, or even another game franchise altogether. RE5, ironically, feels much more like a real sequel to Code Veronica... finally arriving a whopping nine years later.

Not if Capcom has anything to say about it.

Being a story person I tend to want narrative and thematic significance to dictate which games in a franchise are central and which are peripheral. But the Resident Evil franchise, clearly, does not function that way. It seems much more based on gameplay and/or marketing considerations than story. Of course, I wouldn't expect it to be based on story alone, but many game series, like Metal Gear or Half-Life for example, seem to tailor the size and relevance of their stories to the size and relevance of their gameplay innovations, which themselves correspond to the size and relevance of each game's marketing push. Capcom seems to give no shit about this whatsoever in regards to Resident Evil, which is partially what makes the series mythology such a convoluted mess. The result of such a system is that fans have to wait an untold number of years, and be strung along like puppets, while waiting for interesting things to happen in a storyline. And given the frustrating, relatively poor quality of RE's stories, one wonders at the point of even bothering. I certainly do. IndieCade Call for Submissions (Updated)

Updated - note the new deadline of May 15th! Attention students, academics, artists and industry professionals! We'd like to call your attention to the upcoming submission deadline for IndieCade, the upcoming festival of independent games and interactive art being chaired by friend-of-the-lab Celia Pearce. Here's the official CFP.  IndieCade Call for SubmissionsIndieCade invites independent game artists and designers from around the world to submit interactive media of all types - from art to commercial, ARG to abstract, mind-bending to mobile, serious to shooter, as well as academic and student projects - for consideration. Work-in-progress is encouraged. A diverse jury of creative and academic leaders will select entries for top prizes at the IndieCade 2009 Festival. All entries for the Festival will also receive consideration for presentation at all 2009 IndieCade international exhibitions including: IndieCade 2009 Events: Submissions Deadline: For more information and to enter: www.IndieCade.com. IndieCade's successful flagship 2008 festival held last October at Open Satellite contemporary gallery in Bellevue, Washington, was the first major intertaional exhibition of independent videogames and videogame art in the area. Event organizers include IndieCade Founder Stephanie Barish, Chair Celia Pearce, and Festival Director Sam Roberts. Early Baseball Interface Design: a Leadoff Homer

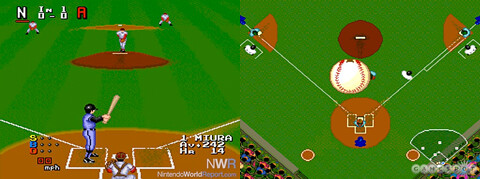

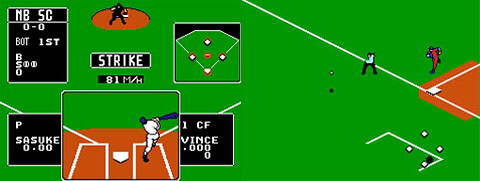

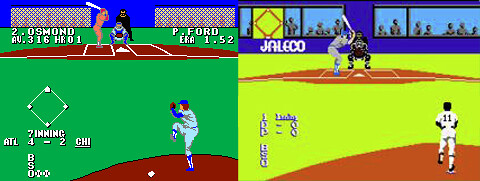

Of all the team sports adapted to computer gaming, only baseball can boast the unrivaled consistency of wearing nearly the same interface for over twenty-five years. As early as 1983, games like Color Baseball for the TRS-80 mapped the cardinal directions of the Tandy Joystick to the four bases of the infield diamond. Color Baseball also featured a top-down view of the entire field that persists in today's lastest games. The context-sensitive control scheme follows the movement of the ball around the field. When a hit leaves the infield, the focus naturally switches to the outfielders. And after a player fields the ball, the position of the joystick indicates to which base it will be thrown. To quote one reviewer, "everything just seems to make sense on-screen." By 1987, the ideal interface for a 2-player computer game adaptation of baseball is firmly in place, as demonstrated by RBI Baseball for the NES. The primary innovation over Color Baseball is the differentiated pitching and fielding scenarios. Like a typical TV broadcast, much of the game is presented as a one-on-one duel between pitcher and hitter. Various statistics and cropped views of the field adorn the central channel but the perspective does not change until either the batter makes contact with a pitch or the pitcher attempts to pick off a baserunner. Notably, both views feature the same orientation such that "down" on the gamepad maps to home plate, "up" maps to second base, and so on.

World Class Baseball for the TurboGrafx-16 improved upon RBI's two perspectives with flyballs that grew significantly larger and left clearly defined shadows on the field as they flew higher, making it much easier for players to judge where and when they might land. Additionally, this title provided fielders with a few fancy leaps and dives without sacrificing the simplicity of the minimal control scheme. As seen above, multiplayer World Class Baseball gameplay hits the right sense of casual pleasure to approximate the sandlot, alleyway pickup game. And who doesn't like the cool Miami take on baseball stadium organ music? Although visual conventions were firmly established in RBI Baseball and World Class Baseball, Baseball Stars is often remembered as the quintessential 1980's baseball title because of its sophisticated statistical system. RBI, like many games, was the product of a licensing arrangement with Major League Baseball and bore the names, logos, and likenesses of real teams and players. Baseball Stars, on the other hand, maintained a Little League baseball fiction in which gamers created their own players and teams that could be stored in cartridge memory and persist across multiple seasons. Rumors abound of hardcore Baseball Stars fans who continue to maintain active teams after two decades of play.

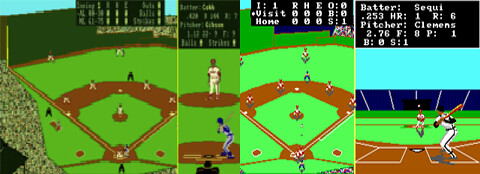

At the end of the 1980s, baseball game designers began to experiment with the traditional interface. Earl Weaver Baseball, primarily a home PC title, offered simultaneous presentation of both perspectives by vertically splitting the screen. Weaver is also notable for its landmark AI, the product of numerous interviews between legendary manager Earl Weaver and the equally legendary game designer Don Daglow who wrote Baseball for the PDP-10 in 1971, the earliest known computer simulation of America's favorite game. Other experiments were less successful. In particular, Roger Clemens MVP Baseball and the Bases Loaded series broke the persistent orientation rule established by earlier titles in an effort to present a more TV-like, multi-angle experience. In each of these games, the "camera angle" swung around such that they broke the dependable relationship between the gamepad's cardinal directions and the baseball diamond's bases. (To get a sense for this disorienting new system, fast-forward the above video to about 1:15.)

The contemporary MLB Power Pros demonstrates the durability of those early baseball game innovations. It features an accumulative statistics system like Baseball Stars, major league licensing and cartoonish character design like RBI Baseball, and the simple play style of World Class Baseball.

While efforts to adapt other sports continue to struggle to find working control schemes, baseball maintains a calm confidence. What are the characteristics of baseball and early console gaming that made effective adaptation possible? In what ways could it have gone off course? Sports gamers tend to be an opinionated bunch. What titles did I miss? My Minions and I

A successful recipe for flash games has been to break off a piece of the real-time strategy genre. Desktop Tower Defense and its ilk focus entirely on the defensive base-building aspect. Games such as Epic War and Age of War are more offensive with the player creating waves of units that march towards the enemy base like lemmings off a cliff. There are plenty of variations on these formulas, and some games incorporate more direct control a la Scorched Earth or Worms. But a new game from Casual Collective (a pair of developers including the creator of DTD) puts a new twist on the micro-RTS. Minions consists of brief (10-15 minute) multiplayer matches where 2-12 players are split between red and blue teams attempt to destroy the opposing color's base. Control is fundamentally similar to an RTS, except that each player only controls a single tank. The tanks are chosen prior to the match from 8 classes, each of which has 3 unique abilities. As time progresses and damage is done to opposing towers, tanks gain experience that with each level increases health, damage, and lets a point be spent upgrading one of the three abilities. The time between re-spawns increases with the player's level. Assisting each team are 4 defensive towers in addition to their home tower and uncontrollable mini-minions sent out periodically. If Puzzle Quest has the scope of a hardcore game with casual mechanics, Casual Collective seems to be attempting the opposite with Minions. Given the single map and relatively small variations between classes (at the mechanics level), Minions is very repetitive yet I can't seem to stop playing. The multiplayer competition ensures that matches are always unique. Although the downside of multiplayer-only is that you always have to deal with other players. And as with any multiplayer game, the players can be a mixed bag. You can't damage players on your own team, but I guarantee there will be times when you wish you could. Sure it's disappointing to be teamed with a noob, but the game is easy enough to learn that they're not noobs for long. The real issue is from players who just don't care. There are no experience points or rankings that continue between matches. You receive some points at the end of match that increase your account's level on the site, but that's a cumulative point total between all games on the site and doesn't impact the games. Not only are there players that wander haphazardly around the map making friends with the walls or taking a 5 minute break, in a majority of matches at least one player will disconnect. And the balance is such that a team with a player-advantage has an almost guaranteed win (assuming they stood a fighting chance previously). Is there a solution to this? A penalty on a player could take away the casually approachable nature of the game. A better method might be to assist the abandoned team. There could be an increase in the power or frequency of mini-minions, or a reduction to that team's re-spawn times. The site's forums are filled with such suggestions but it remains to be seen if Casual Collective is going to spend the time to update the game. Within the last two weeks a much-needed "switch teams" button was added to the lobby screen. But that's the sort of basic feature that should have been included in the first place. Adjusting any sort of balance within the game would be much riskier. Adding a balancing mechanism for players that leave probably wouldn't increase traffic significantly. It's something everyone's used to in online games. There's plenty of talk in the forums about adjusting the classes because of perceived imbalances, but are people not playing because of that? Doubtful. Any time I conclude a class is too powerful, a few matches later I'm proved wrong. It's just a matter of rock-paper-scissors type match-ups. Yeah, three Cutters seem unbeatable when against a group of Docs and Shoutys. But throw in a Splodge and a Stinger and watch the Cutters get torn to pieces. As far as class balance, the only thing that desperately needs to be changed is how extra experience is awarded during a match and how points are calculated at the end. Experience gets a boost from damaging towers, but certain tanks are relatively ineffective against them and are better used to fight back opposing tanks. Points at the end are assigned with some arcane formula based on the ratio of kills to deaths and the damage done to towers. First of all, kills are only measured in killing blows; it doesn't matter if you did 75% of the damage to a whole group of enemies, if you don't land the final blow, you get no credit. Haven't we moved past that in games? Almost all MMORPGs now divide experience among group members based on their contributions, however their class might count that. A healer would even get credit for how much they've healed. But in Minions, the Doc is a pretty thankless class. The Doc is unlikely to do much damage, and has to chase after their teammates who ignore any semblance of formation since the healing ability affects a small radius around the Doc. Adjusting the balance and rewards would be nice, but what the game desperately needs (and should help increase traffic) is more maps. One small map is just not enough. Let's see a brutal maze of towers or a lopsided map for uneven teams. At least rearrange the basic map to create some variation. It can't be that difficult to do. Flash games have the advantage that they can be updated very easily: the webmaster just uploads a new swf file. Being able to instantly release fixes makes full upgrades less important. Why wait for a whole batch of version 1.1 upgrades to release the second map? If there's a fix or a new addition, it can just go straight up. A simple notice on the site about each fix would keep players coming back. I'm no business expert, but when a developer is hosting their own game (or has easy update access), why not avoid "release" versions and just update bit by bit? It seems to work for Google, and they even keep the beta status. The Pleasures of Old School Resident Evil - Battling Rampaging Sex Monsters

While the Resident Evil series has its share of female protagonists, they tend to be less capable than their male counterparts. The female protagonist of RE1, for example, comes equipped with a designated male savior who assists her the entire game. This cycle of the main female protagonist needing to be saved at various points by men is reiterated throughout the series, notably appearing in RE3 and RE: Code Veronica. RE4 doesn't even feature a female protagonist and is instead based entirely around a male protagonist babysitting a helpless teenage girl. Resident Evil 2, interestingly, doesn't feature any such devices and thus feels significantly less misogynistic than the rest of the series. Of RE2's four playable characters--Claire the biker, Ada the spy, Leon the cop, and Sherry the civilian--three of them are female, and two out of those three are not portrayed as being at all submissive or needing help (Sherry being the exception). The lone male playable character, Leon, is not particularly masculine. He has androgynous features, and his attempts to "take charge" get undercut repeatedly by the women in the story. Claire bosses him around most of the time, and Ada repeatedly ignores his advice. ("Why doesn't anyone listen to me?" he laments midway through the game.) Leon is not portrayed as a joke exactly, but he is certainly not a hyper-masculine hero. The rest of the men in RE2's story--sadistic Police Chief Irons, sleazy reporter Ben, and mad scientist William Birkin--are in general selfish, awful people who meet horrid ends. THE CAST OF RESIDENT EVIL 2

It's significant, I think, that the antagonists in RE2 are predominantly male, while the protagonists pitted against them are predominantly female. I am not speaking of the zombies, of course, but the male characters who are the real villains of the story. The most significant of these is Dr. William Birkin, Sherry's father, who has been transformed into a rampaging mutant by a virus he engineered. Birkin spends the entire game chasing after his daughter in a effort to infect her with his virus, which he spreads by attacking people with his writhing, telescopic tentacles. This lingering threat--with its thinly veiled implications of incestual rape--is the real horror at the heart of Resident Evil 2, the horror Claire spends the whole game trying to save Sherry from, the horror that is, in certain ways, much scarier than a mere zombie apocalypse.

|

|

Dr. William Birkin

|

William Berkin is more or less portrayed as a rampaging sexual predator in RE2. Frustrated that he can't find his daughter, he chases down every other character over the course of the story and forces his tentacles down their screaming throats in an attempt to reproduce. The allusions to tentacle porn are obvious, although they become more complicated when one considers that Birkin's victims are almost exclusively male. These men (one of whom is Police Chief Irons, himself a rapist and murderer) are "incompatible" with his DNA and therefore explode as they give birth to new, unbelievably disgusting creatures. Birkin wants to impregnate Sherry because, as someone who shares his DNA, she won't reject the virus... but fuse with it and mutate, like he is. In the terms of the story, Birkin's monster rape rampage is not motivated by sexual desire. Yet from the player's perspective (and Claire's) the horror is obviously sexual. The fact that the over arching narrative is about saving a little girl from being impregnated by her own father is upsetting and impossible to shrug off.

I am not arguing that the sexual politics of RE2 are terribly progressive, only that they are effective. It's true that the goodness and strength of the women in the story is more or less confined to gendered behavior patterns: in Claire's maternal devotion to Sherry and in Ada's romantic devotion to Leon. But RE2 gets thematic and dramatic mileage out of these patterns in ways that other RE games don't. It recalls the effective use of gender and sexuality in the earlier Alien films, specifically Aliens. RE2 is obviously indebted to Aliens for the idea of a warrior woman protecting a little girl from a monsterous sexual threat. But it works in RE2 for pretty much the same reasons it works in Aliens, with the added, far more disturbing layer of actual incest. The fact that RE2 pits such likable anime archetypes against such genuine psychological distress is part of what makes it stand out against the trite garbage of later Resident Evil games.